As I write this, the 83rd Academy Awards ceremony - better known to you and I as the Oscars - is about to begin. I think it is in keeping with the delirious ethos of this blog that the film up for discussion tonight is about as far from Oscar material as it is possible to get (without being porn): an Italian exploitation horror movie.

Italian cinema was notorious for trying various means to exploit the success of recent films or trends. The producers might name their film to make it appear to be the sequel to something when in actual fact it has no relation to the original; a good example is Lucio Fulci's gore classic ZOMBI 2 (1979) - marketed as a sequel to George Romero's DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978), which was called ZOMBI in Italy. The film-makers might take the plot of a successful movie, alter one or two elements and jump right on to the bandwagon; an example of this is Ovidio G. Assonitis' TENTACLES (1977), which is essentially JAWS (1975) with a giant octopus. More brazenly still, the film-makers might just opt for a total rip-off, like Enzo G. Castellari's THE LAST SHARK (1981). In fact, this last example was such a brazen act of theft that Universal sued, and won.

CASTLE OF BLOOD or, to use its original title, DANZA MACABRA (or DANSE MACABRE in my French DVD release version), was directed by Italian genre stalwart Antonio Margheriti in 1964. It purports to be based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe but is no such thing; the Poe angle is merely a ruse to attempt to cash in on the popularity of the Poe adaptations made by Roger Corman, as discussed in earlier posts. True, the film starts with Poe (Silvano Tranquilli) relating one of his stories to travellers at an inn but what follows has nothing to do with the great man.

Another ruse employed by Italian film-makers was to try to disguise the origins of their film, cast and crew in the knowledge that foreign films were often a hard sell to British and particularly American audiences. This didn't just happen to knock-off horror movies but to stone cold classics as well: American audiences would have seen the credits of A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS name the director as 'Bob Robertson' and Ramon as being played by 'Johnny Wels'. One thing that always strikes me about these phoney names for English-speaking markets is that they always sound phoney: they sound like exactly what they are - names made up by people for whom English isn't their first language. So in this film we get the improbable sounding actors 'Henry Kruger', 'Phil Karson', 'Ben Steffen' and my personal favourite 'Montgomery Gleen'.

Once we get all that Poe scene-settery out of the way, the plot is hoary but a good one. Our hero, Alan Foster (played with limited range by George Riviere), a journalist who had arrived to interview Poe, accepts a wager from Lord Blackwood that he cannot spend a single night in the deserted but reputedly haunted Castle Blackwood. Once he arrives, he finds the castle is not as deserted as he had been led to believe. There is a great and lengthy sequence showing Foster making his way into the castle through a passage lit only by his flaming torch.

Whatever Italian genre movies may lack in originality, and however cynical you might think their methods, they are usually great in purely visual terms. Mario Bava was the daddy of this: some of his black-and-white films are genuinely brilliant visually. Antonio Margheriti doesn't quite have Bava's flair but he still has a good eye for a composition and the camerawork is terrific. Some of the shots are almost Expressionistic and bear comparison with Gregg Toland's work on CITIZEN KANE (1941).

The other trump card that Italian genre movies have is that, perhaps because of their unoriginality, they were prepared to go further than their British or American counterparts in depicting scenes of sex and violence. There is a brief topless scene in this movie that would have been unthinkable in a Hammer production of the same year.

I can't discuss this film without mentioning Barbara Steele. As I've posted before, Steele is an icon of the genre and was something of a muse for Italian directors in the 1960s. Few, if any, actresses before or since have personified the idea of unearthly passion as Steele did.

An asylum for the good, the bad, the weird, the cult and the unjustly neglected films that I love.

Monday 28 February 2011

Thursday 24 February 2011

The Tomb of Ligeia (1964)

Okay, so it became a triple-feature in the end. I guess that's because the Poe / Corman series is so atmospheric and of such high quality that you're very keen to see more. Unfortunately this one was something of a disappointment. Maybe I overdid it but, given this film's high reputation, I was expecting more from it.

The final film in the series, this one - unlike all the others - was shot in England and features an all English cast, with the exception of Vincent Price as Verden Fell. I suspect that may be part of the problem because although some of the customary Poe / Corman themes and elements are there, it looks and feels more like a Hammer film.

One other problem, and I confess this is more of a personal taste issue, and something I wish all film-makers would take heed of is this - Cats. Are. Not. Frightening. Small furry creatures are by definition not frightening. I haven't seen THE KILLER SHREWS but I suspect it wouldn't give me sleepless nights; neither have I seen NIGHT OF THE LEPUS but the clips on YouTube suggest that killer rabbits are less than terrifying. Cats are exactly the same. Cruel and independent animals they might be, but fearsome they are not. So, given that this film centres around the premise that Verden Fell's late wife may or may not have been reincarnated as a vengeful cat, it is on to a loser from the word go.

The film builds up a fair head of steam at times only for the effect to be utterly diminished by someone out of shot throwing a cat - or worse still a stuffed cat - into shot for the poor actors to wrestle with. Either that or there is a shot, for example, of an actor creeping up towards a door and as we wait in fearful anticipation of what might be beyond it all your hear is a cat's meow as if someone has just booted a truculent moggy down a flight of stairs.

It's a pity because there are some good things going on amid the feline buffoonery. It's another high gothic tale of demented love and features a great performance from Elizabeth Shepherd as the woman who falls foul of Ligeia's jealousy. On the whole, parts for women in horror films are pretty dreadful - usually either one-dimensionally evil or pure - but Shepherd plays Rowena Trevanion as an intelligent, independent and sexually aware woman.

The script, by Robert Towne (CHINATOWN) and an uncredited Paul Mayersberg (THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH), is pretty good: it's perhaps too wordy at times but it's never less than literate and captures the feel of Poe's prose well. The location shooting at Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk is unusual and atmospheric and, as you would expect from Corman, some of the art direction is great - notably a fabulous red carpet that spills out of a corridor and down a flight of steps as if a wave of blood has gushed forth.

The final film in the series, this one - unlike all the others - was shot in England and features an all English cast, with the exception of Vincent Price as Verden Fell. I suspect that may be part of the problem because although some of the customary Poe / Corman themes and elements are there, it looks and feels more like a Hammer film.

One other problem, and I confess this is more of a personal taste issue, and something I wish all film-makers would take heed of is this - Cats. Are. Not. Frightening. Small furry creatures are by definition not frightening. I haven't seen THE KILLER SHREWS but I suspect it wouldn't give me sleepless nights; neither have I seen NIGHT OF THE LEPUS but the clips on YouTube suggest that killer rabbits are less than terrifying. Cats are exactly the same. Cruel and independent animals they might be, but fearsome they are not. So, given that this film centres around the premise that Verden Fell's late wife may or may not have been reincarnated as a vengeful cat, it is on to a loser from the word go.

|

| Terrifying, isn't it? |

|

| The horror, the horror. |

|

| This, believe it or not, is the climactic scene. |

|

| Elizabeth Shepherd as Rowena Trevanion |

|

| Castle Acre Priory |

|

| Rivers of blood |

Wednesday 23 February 2011

Nicholas Courtney (1929 - 2011)

We're not big DR WHO fans here at Cinema Delirium - it doesn't really qualify as 'delirious' because it's too mainstream and already celebrated by more than enough people online and off - but it's only right to mention the passing of Nicholas Courtney, who is fondly remembered for playing Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart. Quite apart from his sterling work on that programme his CV features more than enough delirious entries to qualify anyway.

He appeared in Don Sharp's THE BRIDES OF FU MANCHU, one of a series that began well and got increasingly delirious as notorious hack / auteur (delete according to taste) Jess Franco got his hands on it. On top of that he had parts in films such as JOURNEY TO THE FAR SIDE OF THE SUN, Jonathan Miller's TAKE A GIRL LIKE YOU with the always delirious Oliver Reed, and Roy Boulting's SOFT BED, HARD BATTLES with Peter Sellers. He was also in episodes of DOOMWATCH, THE AVENGERS, THE SAINT, JASON KING, CALLAN and RANDALL & HOPKIRK (DECEASED) and something called THE RIVALS OF SHERLOCK HOLMES, which I've not seen but it sounds intriguing - which, along with DR WHO, is pretty much all of your classic '70s series.

So we offer a salute, in every sense, to the wonderfully delirious career of Nicholas Courtney.

He appeared in Don Sharp's THE BRIDES OF FU MANCHU, one of a series that began well and got increasingly delirious as notorious hack / auteur (delete according to taste) Jess Franco got his hands on it. On top of that he had parts in films such as JOURNEY TO THE FAR SIDE OF THE SUN, Jonathan Miller's TAKE A GIRL LIKE YOU with the always delirious Oliver Reed, and Roy Boulting's SOFT BED, HARD BATTLES with Peter Sellers. He was also in episodes of DOOMWATCH, THE AVENGERS, THE SAINT, JASON KING, CALLAN and RANDALL & HOPKIRK (DECEASED) and something called THE RIVALS OF SHERLOCK HOLMES, which I've not seen but it sounds intriguing - which, along with DR WHO, is pretty much all of your classic '70s series.

So we offer a salute, in every sense, to the wonderfully delirious career of Nicholas Courtney.

Tuesday 22 February 2011

The Pit and the Pendulum (1961)

Having enjoyed Vincent Price in THE LAST MAN ON EARTH, I decided to make it a double-feature with THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM. Made three years earlier, this was the second in the justly renowned series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations directed by Roger Corman for American International Pictures (AIP). The series is noted for its style and imagination, impressive sets and design, vivid use of colour and scripts that were superior to most genre pictures of the time.

In actual fact the connection to Poe is nominal in this case, the story being devised by Richard Matheson (him again). Nevertheless, some very Poe elements are in there: isolated, gloomy and rambling old house; tormented master of the estate; depraved family history; young intruder; premature burial; madness and death. Heady stuff indeed.

Even before the opening titles have been revealed there is a striking abstract sequence which (I presume) uses coloured lights and oils:

This is typical of the Poe / Corman series and in a way symbolises their atmosphere: lurid, dreamlike and disturbing. These films aren't frightening in the sense that, say, THE EXORCIST or even THE FOG are frightening. In fact one could argue that, much like the Hammer films, when viewed today they aren't frightening in any sense. However, unlike the Hammer films which tend to rely on nostalgia and fond recollection for their impact, Corman's films retain some of their original power because the 'monsters' are human beings. Poe's characters were sickly, obsessed people whose depravity was only thinly masked by their aristocratic breeding. Indeed, in some cases their aristocratic background was the cause of their problems.

I understand that the budget was higher for these films than was normally the case with AIP which is undoubtedly why they still look impressive today. Although the modern audience would be able to instantly identify the matte shots (where live-action footage is combined with a painting on glass to form a composite image) they are still impressive for the skill with which they have been executed. There is a good example in the opening sequence:

Here the beach and sea are live-action but the cliffs, castle and sky are painted. Quite obviously not real but a superb image all the same. There is another fine example in the climactic pit and pendulum sequence:

Again, the actors are shot in the normal way and the footage is integrated with the painting of the pit and surrounding building to great effect.

Similarly, the sets - which to the modern eye will look like imitations - have been designed and constructed with flair and skill. Corman obviously spent his money well because there are lots of different sets and they are on a large scale, which helps to create the impression of a vast and perhaps not entirely explored castle. I suspect they are intended to represent Nicholas Medina's (Vicnent Price) mind, or at least his subconscious mind. As the camera prowls down empty corridors and down dusty staircases, into cobwebbed chambers and dungeons, the narrative is simultaneously taking us into Medina's nightmarish memories.

Incidentally, during a couple of flashback sequences, we do actually enter Medina's past and this is indicated by an eerie use of colour:

There's a lot to enjoy in the Poe / Corman series; the best is probably THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH but this one is also excellent. Medina's final descent into madness, the brink of which he has been teetering on since the film began, is at once chilling and pitiful. For cinephiles there is also plenty to look out for. Barbara Steele, who plays Medina's wife, is another genre movie icon. She starred in Mario Bava's debut feature THE MASK OF SATAN and possessed one of the most striking faces in all of cinema.

I saw her interviewed by Mark Gatiss in his recent documentary series on horror and she still looks terrific. She was described once as 'the only woman whose eyebrows could snarl' which is a great expression. Also in the cast is Luana Anders who most people won't know but she had small roles in a lot of good films in the 1960s and '70s. She was a member of the AIP stock company and was good friends with Jack Nicholson. She died in 1996 but Nicholson saw fit to mention her in his Oscar acceptance speech the following year. The aforementioned art direction was by Daniel Haller, who went on to direct films in his own right, including the flawed but interesting H. P. Lovercraft adaptation THE DUNWICH HORROR.

I can't resist closing this piece with a still of the film's final, haunting image:

In actual fact the connection to Poe is nominal in this case, the story being devised by Richard Matheson (him again). Nevertheless, some very Poe elements are in there: isolated, gloomy and rambling old house; tormented master of the estate; depraved family history; young intruder; premature burial; madness and death. Heady stuff indeed.

Even before the opening titles have been revealed there is a striking abstract sequence which (I presume) uses coloured lights and oils:

This is typical of the Poe / Corman series and in a way symbolises their atmosphere: lurid, dreamlike and disturbing. These films aren't frightening in the sense that, say, THE EXORCIST or even THE FOG are frightening. In fact one could argue that, much like the Hammer films, when viewed today they aren't frightening in any sense. However, unlike the Hammer films which tend to rely on nostalgia and fond recollection for their impact, Corman's films retain some of their original power because the 'monsters' are human beings. Poe's characters were sickly, obsessed people whose depravity was only thinly masked by their aristocratic breeding. Indeed, in some cases their aristocratic background was the cause of their problems.

I understand that the budget was higher for these films than was normally the case with AIP which is undoubtedly why they still look impressive today. Although the modern audience would be able to instantly identify the matte shots (where live-action footage is combined with a painting on glass to form a composite image) they are still impressive for the skill with which they have been executed. There is a good example in the opening sequence:

Here the beach and sea are live-action but the cliffs, castle and sky are painted. Quite obviously not real but a superb image all the same. There is another fine example in the climactic pit and pendulum sequence:

Again, the actors are shot in the normal way and the footage is integrated with the painting of the pit and surrounding building to great effect.

Similarly, the sets - which to the modern eye will look like imitations - have been designed and constructed with flair and skill. Corman obviously spent his money well because there are lots of different sets and they are on a large scale, which helps to create the impression of a vast and perhaps not entirely explored castle. I suspect they are intended to represent Nicholas Medina's (Vicnent Price) mind, or at least his subconscious mind. As the camera prowls down empty corridors and down dusty staircases, into cobwebbed chambers and dungeons, the narrative is simultaneously taking us into Medina's nightmarish memories.

Incidentally, during a couple of flashback sequences, we do actually enter Medina's past and this is indicated by an eerie use of colour:

There's a lot to enjoy in the Poe / Corman series; the best is probably THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH but this one is also excellent. Medina's final descent into madness, the brink of which he has been teetering on since the film began, is at once chilling and pitiful. For cinephiles there is also plenty to look out for. Barbara Steele, who plays Medina's wife, is another genre movie icon. She starred in Mario Bava's debut feature THE MASK OF SATAN and possessed one of the most striking faces in all of cinema.

I saw her interviewed by Mark Gatiss in his recent documentary series on horror and she still looks terrific. She was described once as 'the only woman whose eyebrows could snarl' which is a great expression. Also in the cast is Luana Anders who most people won't know but she had small roles in a lot of good films in the 1960s and '70s. She was a member of the AIP stock company and was good friends with Jack Nicholson. She died in 1996 but Nicholson saw fit to mention her in his Oscar acceptance speech the following year. The aforementioned art direction was by Daniel Haller, who went on to direct films in his own right, including the flawed but interesting H. P. Lovercraft adaptation THE DUNWICH HORROR.

I can't resist closing this piece with a still of the film's final, haunting image:

Sunday 20 February 2011

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

I'll come right out with it: I love post-apocalypse / end of the world movies. I can't get enough of them, so I'm fortunate that there are plenty around at the moment. I also like the same themes in literature and, again, there are more examples than I have time to read. One undisputed masterpiece of the genre is Richard Matheson's "I Am Legend" which was first published in 1954. It's so good that it has served as the basis for at least four films and has inspired many others. The film in question here is the first of those adaptations and was directed by someone called Sidney Salkow about whom I know very little.

I've seen three and a bit of those adaptations and this one is the closest to the novel. Apart from a slightly altered ending it's remarkably faithful, even including the episode with the dog and the origin of the novel's strange but powerful title. The reason for this is that Matheson wrote the screenplay, a fact I only discovered this from watching a short interview with him on the disc, because the screenplay is actually credited to 'Logan Swanson'. Apparently this was because Matheson wasn't happy with the way the film was going and wanted to remove his name from the credits entirely; on being told that that would mean he wouldn't get any residuals from the film he decided to go for a pseudonym instead. The name derives from the maiden names of his mother and his wife's mother.

I'm not sure what Matheson's problem was because, as I said, it's faithful to the source material. One drawback is that despite being set in the US it was filmed in Italy (presumably because it was easier to film the deserted city scenes) so it doesn't quite convince. Similarly, apart from Vincent Price as Robert Morgan (annoyingly and pointlessly renamed from Robert Neville in the book), the rest of the cast are Italian, including delirious movie stalwart Giacomo Rossi-Stuart as Morgan's nemesis. Now there's nothing wrong with Italian actors but they've all been dubbed with American voices so it just doesn't seem quite right. Maybe those things annoyed Matheson, I don't know.

Those points aside, it's rather good. I liked that Morgan's house was a hovel, unlike the palatial accomodation enjoyed by Charlton Heston and Will Smith in THE OMEGA MAN and I AM LEGEND respectively. Let's face it, if you were the last man on Earth with little prospect of anyone coming round for tea you wouldn't bother too much about hoovering or dusting would you?

I thought the burning pit of hell where the infected corpses were destroyed was a strong image.

The vampires were good too: weak, as they would be, and almost zombie-like. The scenes of them attacking Morgan's house could well have influenced George Romero's NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, which resembles this closely.

Vincent Price was a great actor - a bit hammy at times maybe but he had a fabulous voice and a wonderfully expressive face. He's almost the quintessential delirious actor and had a long and distinguished career in genre movies; his best performances are too numerous to mention. In some ways he is the American Peter Cushing: a refined and cultured man who happened to be very good at playing horrific roles. Like Cushing, he never appeared to think he was above the material, giving his all whatever the film's quality. It's good to see him in a rare heroic role in this film, although he plays it with his customary haunted intensity.

I've seen three and a bit of those adaptations and this one is the closest to the novel. Apart from a slightly altered ending it's remarkably faithful, even including the episode with the dog and the origin of the novel's strange but powerful title. The reason for this is that Matheson wrote the screenplay, a fact I only discovered this from watching a short interview with him on the disc, because the screenplay is actually credited to 'Logan Swanson'. Apparently this was because Matheson wasn't happy with the way the film was going and wanted to remove his name from the credits entirely; on being told that that would mean he wouldn't get any residuals from the film he decided to go for a pseudonym instead. The name derives from the maiden names of his mother and his wife's mother.

I'm not sure what Matheson's problem was because, as I said, it's faithful to the source material. One drawback is that despite being set in the US it was filmed in Italy (presumably because it was easier to film the deserted city scenes) so it doesn't quite convince. Similarly, apart from Vincent Price as Robert Morgan (annoyingly and pointlessly renamed from Robert Neville in the book), the rest of the cast are Italian, including delirious movie stalwart Giacomo Rossi-Stuart as Morgan's nemesis. Now there's nothing wrong with Italian actors but they've all been dubbed with American voices so it just doesn't seem quite right. Maybe those things annoyed Matheson, I don't know.

Those points aside, it's rather good. I liked that Morgan's house was a hovel, unlike the palatial accomodation enjoyed by Charlton Heston and Will Smith in THE OMEGA MAN and I AM LEGEND respectively. Let's face it, if you were the last man on Earth with little prospect of anyone coming round for tea you wouldn't bother too much about hoovering or dusting would you?

I thought the burning pit of hell where the infected corpses were destroyed was a strong image.

The vampires were good too: weak, as they would be, and almost zombie-like. The scenes of them attacking Morgan's house could well have influenced George Romero's NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, which resembles this closely.

Vincent Price was a great actor - a bit hammy at times maybe but he had a fabulous voice and a wonderfully expressive face. He's almost the quintessential delirious actor and had a long and distinguished career in genre movies; his best performances are too numerous to mention. In some ways he is the American Peter Cushing: a refined and cultured man who happened to be very good at playing horrific roles. Like Cushing, he never appeared to think he was above the material, giving his all whatever the film's quality. It's good to see him in a rare heroic role in this film, although he plays it with his customary haunted intensity.

Saturday 19 February 2011

Theorem (1968)

Well now. This is ramping things up a notch. As much a statement of personal philosophy as it is a film, this was directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini during a particularly fertile period for European cinema. I can't remember who said it but someone once remarked that in Hollywood, films are regarded as a commercial entity with marginal artistic potential, and that in Europe films are regarded as an artistic entity with marginal commercial potential. THEOREM (or TEOREMA, to use the original Italian title) demonstrates the second part of that statement perfectly, being nothing less than an attack on capitalism and bourgeois values.

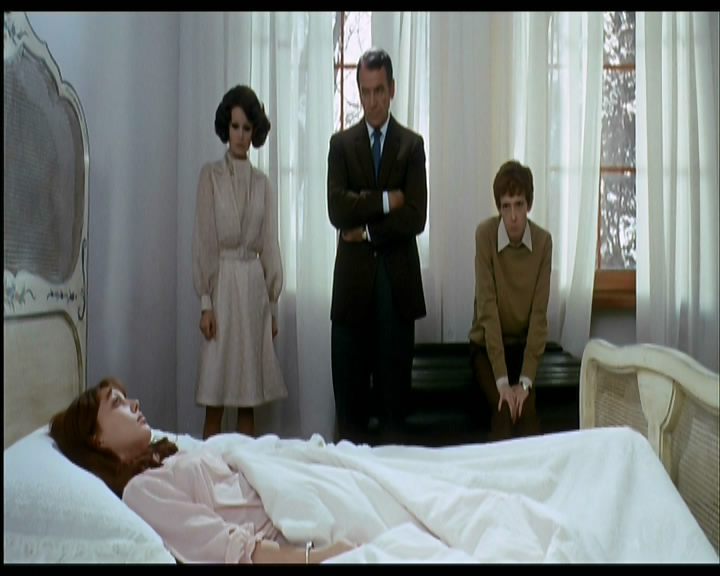

Perhaps it's best to briefly describe the plot, or more accurately the structure, since there is no 'story' as such being told here. We see the members of a wealthy Milanese household: the father, a factory owner, the wife, the son, the daughter and the housekeeper. A young man arrives to stay for a few days. In turn, each member of the family finds the young man an overwhelming and inspiring simply by his presence. As abruptly as he arrived, he leaves. The family members are bereft and each fins their life irrevocably changed.

Pasolini was an uncompromising man in life and his films reflect that. THEOREM makes absolutely no concession to accessibility or to spell out its message in simple terms. As a result, its meaning - assuming there is one - has been speculated over endlessly. Knowing a little about Pasolini's life and politics, and having read a little about the film, this is my take on it. It's a crude interpretation, and cobbled together from various sources, but it's how I have made sense for myself out of a difficult film.

At the beginning of the film there is a quote from Exodus: "God led the people about, through the way of the wilderness."

Subsequent to that we are introduced to the bourgeois family in a sepia sequence perhaps intended to emphasise how deeply rooted bourgeois values are.

I think Pasolini intends us to see bourgeois values, and adherence to capitalism, as 'the wilderness'. Into this wilderness comes the stranger, played by Terence Stamp.

Stamp was, and still is, a very good looking guy and since the film is largely silent I assume he was cast for his looks and presence as muich as his acting ability. An interview on the disc appears to cofirm that as Stamp relates a chance meeting with Silvana Mangano (who plays the mother) and Pasolini in Rome, with Mangano remarking that he would be perfect for the role.

The young man is a serene and calming presence, and seductive in a non-sexual way. All of the family members fall deeply in love with him and, just before he leaves, they confess to him that he has changed them in ways they never though possible and that they will be distraught without him. In other words they have each experienced a moment of epiphany. Obviously it's tempting, therefore, to see Stamp's character as a Christ figure but because Pasolini was an atheist I think the character represents a non-specific spiritual presence.

I think that their awakening reveals to them the emptiness of their lives and the meaninglessness of their wealth and property. They react in different ways to this new awareness. The housekeeper immediately leaves Milan and returns to her family somewhere in rural Italy. There she sits on a bench and refuses to move. After some time it appears that she is able to perform miracles.

The mother seeks solace in random and sordid sexual encounters with young men, who presumably remind her of the visitor.

The son finds himself driven to express his love for the visitor through art, which becomes progressively more abstract as he struggles to find a way to communicate his adoration.

The daughter finds her grief impossible to bear and retreats into a catatonic state. She is eventually taken to an asylum.

And the father gives his factory to the workers and literally divests himself of every trapping of materialism, by removing his clothes at a railway station and wandering off into the wilderness - the same mountainside seen at the beginning of the film. That tends to support my view that Pasolini sees the factory, representing the source of the man's wealth through exploitation of the workers. In reaching the mountain, the man has been reborn.

So is Pasolini arguing for a greater spirituality in Italian society? I don't think so. I think he is arguing the need for the rejection of the well-established order and for a mass re-awakening of the individual to benefit society as a whole.

There you go - as I said, a crude interpretation but it does serve to extract some meaning from a very good but difficult film. I expect I will return to this one in future, so keep your eyes peeled for further posts. In the meantime, there is a lengthy analysis of the film here.

A few cineaste points to note. Laura Betti, who plays the housekeeper, featured in a couple of Mario Bava's films, as did Massimo Girotti, who plays the father, although I think his greatest role was the lover in Luchino Visconti's version of "The Postman Always Rings Twice", called OSSESSIONE (1943). I think it's interesting that Italian actors seemed able to move from highbrow films such as THEOREM and genre films like Bava's. It's not something that happens a lot in British film-making; it's hard to imagine, for instance, Dame Judi Dench appearing in some low budget, blood-soaked horror movie. Anna Wiazemsky, who plays the daughter, was married to Jean-Luc Godard who was perhaps the French equivalent of Pasolini in his refusal to compromise in his films or philosophy. Ennio Morricone, perhaps the greatest film composer of them all, provided the soundtrack. A final word on Terence Stamp, whom I had the great fortune to meet at a film screening in Birmingham many years ago. He may not have been the greatest actor in the world, but he was better than some credit him, and perhaps more importantly usually appeared in interesting films.

Perhaps it's best to briefly describe the plot, or more accurately the structure, since there is no 'story' as such being told here. We see the members of a wealthy Milanese household: the father, a factory owner, the wife, the son, the daughter and the housekeeper. A young man arrives to stay for a few days. In turn, each member of the family finds the young man an overwhelming and inspiring simply by his presence. As abruptly as he arrived, he leaves. The family members are bereft and each fins their life irrevocably changed.

Pasolini was an uncompromising man in life and his films reflect that. THEOREM makes absolutely no concession to accessibility or to spell out its message in simple terms. As a result, its meaning - assuming there is one - has been speculated over endlessly. Knowing a little about Pasolini's life and politics, and having read a little about the film, this is my take on it. It's a crude interpretation, and cobbled together from various sources, but it's how I have made sense for myself out of a difficult film.

At the beginning of the film there is a quote from Exodus: "God led the people about, through the way of the wilderness."

|

| Which is the wilderness? This ... |

|

| ... or this - the father's factory? |

I think Pasolini intends us to see bourgeois values, and adherence to capitalism, as 'the wilderness'. Into this wilderness comes the stranger, played by Terence Stamp.

Stamp was, and still is, a very good looking guy and since the film is largely silent I assume he was cast for his looks and presence as muich as his acting ability. An interview on the disc appears to cofirm that as Stamp relates a chance meeting with Silvana Mangano (who plays the mother) and Pasolini in Rome, with Mangano remarking that he would be perfect for the role.

The young man is a serene and calming presence, and seductive in a non-sexual way. All of the family members fall deeply in love with him and, just before he leaves, they confess to him that he has changed them in ways they never though possible and that they will be distraught without him. In other words they have each experienced a moment of epiphany. Obviously it's tempting, therefore, to see Stamp's character as a Christ figure but because Pasolini was an atheist I think the character represents a non-specific spiritual presence.

I think that their awakening reveals to them the emptiness of their lives and the meaninglessness of their wealth and property. They react in different ways to this new awareness. The housekeeper immediately leaves Milan and returns to her family somewhere in rural Italy. There she sits on a bench and refuses to move. After some time it appears that she is able to perform miracles.

The mother seeks solace in random and sordid sexual encounters with young men, who presumably remind her of the visitor.

The son finds himself driven to express his love for the visitor through art, which becomes progressively more abstract as he struggles to find a way to communicate his adoration.

The daughter finds her grief impossible to bear and retreats into a catatonic state. She is eventually taken to an asylum.

And the father gives his factory to the workers and literally divests himself of every trapping of materialism, by removing his clothes at a railway station and wandering off into the wilderness - the same mountainside seen at the beginning of the film. That tends to support my view that Pasolini sees the factory, representing the source of the man's wealth through exploitation of the workers. In reaching the mountain, the man has been reborn.

So is Pasolini arguing for a greater spirituality in Italian society? I don't think so. I think he is arguing the need for the rejection of the well-established order and for a mass re-awakening of the individual to benefit society as a whole.

There you go - as I said, a crude interpretation but it does serve to extract some meaning from a very good but difficult film. I expect I will return to this one in future, so keep your eyes peeled for further posts. In the meantime, there is a lengthy analysis of the film here.

A few cineaste points to note. Laura Betti, who plays the housekeeper, featured in a couple of Mario Bava's films, as did Massimo Girotti, who plays the father, although I think his greatest role was the lover in Luchino Visconti's version of "The Postman Always Rings Twice", called OSSESSIONE (1943). I think it's interesting that Italian actors seemed able to move from highbrow films such as THEOREM and genre films like Bava's. It's not something that happens a lot in British film-making; it's hard to imagine, for instance, Dame Judi Dench appearing in some low budget, blood-soaked horror movie. Anna Wiazemsky, who plays the daughter, was married to Jean-Luc Godard who was perhaps the French equivalent of Pasolini in his refusal to compromise in his films or philosophy. Ennio Morricone, perhaps the greatest film composer of them all, provided the soundtrack. A final word on Terence Stamp, whom I had the great fortune to meet at a film screening in Birmingham many years ago. He may not have been the greatest actor in the world, but he was better than some credit him, and perhaps more importantly usually appeared in interesting films.

Friday 18 February 2011

Death Walks on High Heels [1971]

As if to demonstrate that I do actually possess some discernment and don't think every film I watch is wonderful, along comes Luciano Ercoli's DEATH WALKS ON HIGH HEELS. Those of you who have been paying attention may already have guessed from its bizarre title that this is another example of the giallo. Unfortunately it is a particularly inept example.

All the elements are there but they are put together with such a lazy and cynical disregard for the audience, as though the film-makers think all they have to do is dream up a convoluted plot, add a dash of gore and a whole heap of nudity and the audiences will come running. It misses the whole point of the giallo which is style; it is such a robust genre that it can bear any amount of sleaze or bad taste, as long as it is carried off with style. Very little of that style is in evidence here, so the film comes off as merely tawdry. Furthermore, in tacit acceptance that the film is floundering, the director goes for some very broad comedy which doesn't work at all. To make matters worse the film is set largely in an English coastal village. This isn't a problem in itself until you consider that most of the cast are swarthy foreigners, which leads to some rather odd looking characters.

There is very little else to add apart from noting the presence of Frank Wolff, the sole English actor in the cast, who worked almost exclusively on the continent, most memorably in Sergio Leone's epic ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST.

He's actually not too bad in this, giving a better performance than the script deserves. How can you take seriously a line such as "I'll be back tomorrow to talk to Captain Lenny about the boat, but then I'll have to rush off again as I've got to do a pretty delicate eye operation on a man who's losing his sight."

All the elements are there but they are put together with such a lazy and cynical disregard for the audience, as though the film-makers think all they have to do is dream up a convoluted plot, add a dash of gore and a whole heap of nudity and the audiences will come running. It misses the whole point of the giallo which is style; it is such a robust genre that it can bear any amount of sleaze or bad taste, as long as it is carried off with style. Very little of that style is in evidence here, so the film comes off as merely tawdry. Furthermore, in tacit acceptance that the film is floundering, the director goes for some very broad comedy which doesn't work at all. To make matters worse the film is set largely in an English coastal village. This isn't a problem in itself until you consider that most of the cast are swarthy foreigners, which leads to some rather odd looking characters.

|

| The oddjob man and the barmaid. English as ... antipasti |

|

| Inspectors Bergson and Baxter of the Polizia ... I mean 'the Yard'. |

|

| Frank Wolff |

Thursday 17 February 2011

The Black Belly of the Tarantula (1971)

Although no great shakes in itself, this film is instructive because it typifies a sub-genre which figures large in delirious cinema - the giallo. The giallo is a type of thriller with very defined elements, which takes its name from the yellow covers of pulp crime novels in Italy. Essentially a whodunnit, the giallo generally has a series of murders committed by a masked or fleetingly-seen villain who uses a cruel or unusual method of dispatching his victims and is not unmasked until the climax. The hero, sometimes a journalist or a relative of the first victim, struggles to identify the culprit but hits on a key clue just before the end, leading to a final confrontation. Having said all that, what sets the giallo apart from more mainstream thrillers is that the plot is simply a vehicle for a series of stylish and often violent set-piece sequences, set to often excellent soundtracks by the likes of Ennio Morricone and Stelvio Cipriani.

Giallo films started in the early 60s in Italy with films by Mario Bava who was influenced by Hitchcock, and flourished toward the end of the decade and in to the 70s. Dario Argento (Argento and Bava are two names you will hear a lot on this blog, being as they are two colossi of delirious cinema) made his name with a series of gialli in the early 70s which, because of their success and the copycat nature of a lot of Italian genre films, pretty much set the template for those that followed. One great feature of the gialli is that they usually have great titles: Argento's first film was THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (1970) followed by CAT O'NINE TAILS (1971) and FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET (1971). A lot of animal-themed titles followed as unscrupulous Italian producers and distributors caught on to the new craze. I think my favourite giallo title though is Sergio Martino's YOUR VICE IS A LOCKED DOOR AND ONLY I HAVE THE KEY (1972).

However, a couple of things to bear in mind about titles is, first, that they are often merely allusive and second that any given film can be known by a number of different titles, because they were often retitled to suit the different countries in which they were marketed. For instance, the Sergio Martino film mentioned above has 9 alternative titles listed on imdb. Titling can be a minefield in delirious cinema and is probably worth a post in its own right.

Anyway, back to THE BLACK BELLY OF THE TARANTULA which was directed by Paolo Cavara in 1971. This was really in the first wave of films that were made pretty much to cash in on the popularity of the giallo and was picked up for distribution in the US by MGM, which shows that even the big American studios could see their appeal. The plot concerns a series of murders, naturally, that centre around a beauty salon. Which of course gives Cavara the opportunity to show lots of female flesh, an opportunity he grabs with both hands, so to speak.

A common feature of Italian genre movies is the casting of fading stars and European starlets. This film is no exception, featuring as it does not one, not two but three former or future Bond girls in Claudine Auger (THUNDERBALL), Barbara Bouchet (CASINO ROYALE) and Barbara Bach (THE SPY WHO LOVED ME). The film geek in me wonders whether any film outside the Bond canon has featured so many Bond girls.

The method employed by the murderer in this particular giallo is that he first injects his victims with poison so that they are paralyzed but conscious and then finishes them off with a knife. Sounds gruesome I know but the violence in this film is pretty tame by the standards of Italian genre cinema. The method is important though because another feature of the giallo is the fetishisation of weaponry - which is almost always seen being handled by the gloved hands of the murderer - in this case the massive needle used to inject the poison.

So what we get is essentially a series of murders intercut with scenes of the investigation - in this case led by a detective, played by Giancarlo Giannini - who has been in a lot of very good films and occasionally crops up in an English-speaking role, notably in the remake of CASINO ROYALE (another Bond connection) and HANNIBAL. There is a chase sequence across rooftops (leading to a gloriously fake dummy being thrown off), the customary Italian gallery of grotesques and a satisfying ending.

All in all then, not a brilliant giallo but a useful one because it contains so many of the elements that make the sub-genre what it is. More, and better, gialli will feature on this blog in future posts.

Watch the trailer here:

|

| Italian cinema recycling famous film imagery |

However, a couple of things to bear in mind about titles is, first, that they are often merely allusive and second that any given film can be known by a number of different titles, because they were often retitled to suit the different countries in which they were marketed. For instance, the Sergio Martino film mentioned above has 9 alternative titles listed on imdb. Titling can be a minefield in delirious cinema and is probably worth a post in its own right.

Anyway, back to THE BLACK BELLY OF THE TARANTULA which was directed by Paolo Cavara in 1971. This was really in the first wave of films that were made pretty much to cash in on the popularity of the giallo and was picked up for distribution in the US by MGM, which shows that even the big American studios could see their appeal. The plot concerns a series of murders, naturally, that centre around a beauty salon. Which of course gives Cavara the opportunity to show lots of female flesh, an opportunity he grabs with both hands, so to speak.

A common feature of Italian genre movies is the casting of fading stars and European starlets. This film is no exception, featuring as it does not one, not two but three former or future Bond girls in Claudine Auger (THUNDERBALL), Barbara Bouchet (CASINO ROYALE) and Barbara Bach (THE SPY WHO LOVED ME). The film geek in me wonders whether any film outside the Bond canon has featured so many Bond girls.

|

| Auger (left) and Bach |

So what we get is essentially a series of murders intercut with scenes of the investigation - in this case led by a detective, played by Giancarlo Giannini - who has been in a lot of very good films and occasionally crops up in an English-speaking role, notably in the remake of CASINO ROYALE (another Bond connection) and HANNIBAL. There is a chase sequence across rooftops (leading to a gloriously fake dummy being thrown off), the customary Italian gallery of grotesques and a satisfying ending.

|

| Inspector Tellini (right) investigates |

Watch the trailer here:

Wednesday 16 February 2011

Le Cercle Rouge (1970)

Le Cercle Rouge is a heist movie, made by French director Jean-Pierre Melville in 1970. It's fabulous, as are all the films of his that I've seen. Melville began making crime movies in the 1950s and from the outset was as much interested in the iconography of crime and gangsters as he was in the story. By 1970 he had more or less stripped the story back to its bare bones, leaving recognisable elements in an almost abstract setting. In Le Cercle Rouge we learn almost nothing about the criminals, no attempt is made to explain or justify what they do and no moral position is taken. In Melville's world men simply do what they do.

The film begins with a quote attributed to Buddha but apparently an inventon of Melville himself. It says:

'When men, even unknowingly, are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever the diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.'

So this is about fate, or the impossibility of escaping one's fate. The quote is reinforced throughout the film via a subtle but constant series of visual reminders. For instance, the opening sequence sees Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté) being escorted on to a train by Commissioner Mattei, who is presumably taking him to jail. Trains have long been used as signifiers of an inescapable fate because they represent a defined path from which you can't divert: in Zola's 'La Bête Humaine' for example and also in NORTH BY NORTHWEST, among many other films.

Even when he managers to get off the train, Vogel finds himself trapped by his environment:

Similarly, Alain Delon's characater Corey starts the film in jail but finds the outside world to be just as restrictive:

This visual motif of vertical lines is there throughout the film, and not always as obviously as the two examples above. It's there in the billiard hall for instance:

And in Jansen's (Yves Montand) hyper-stylised room:

The heist sequence itself, at a jewellery store in the Place Vendôme, is a masterpiece. Like I said before, Melville has made an almost abstract film so the heist is carried out in silence, except for one word, it lasts almost half an hour and is absolutely rivetting. You're almost invited to see the criminals carrying out their work as a form of self-expression.

Imagine a modern action movie having a silent sequence that long. Speaking of which, I understand a remake is planned, with Orlando Bloom in the Alain Delon role and also starring Liam Neeson who, by my reckoning hasn't made a good film in nearly 20 years. It might be good, it might even be very good, but I can promise you it won't be as good as the original. Both Volonté (who played sweaty villains in two of the Eastwood / Leone westerns) and Delon are genuine icons of European cinema and Meville was, within his self-imposed limitations, approaching genius.

You can see the trailer here:

The film begins with a quote attributed to Buddha but apparently an inventon of Melville himself. It says:

'When men, even unknowingly, are to meet one day, whatever may befall each, whatever the diverging paths, on the said day, they will inevitably come together in the red circle.'

So this is about fate, or the impossibility of escaping one's fate. The quote is reinforced throughout the film via a subtle but constant series of visual reminders. For instance, the opening sequence sees Vogel (Gian Maria Volonté) being escorted on to a train by Commissioner Mattei, who is presumably taking him to jail. Trains have long been used as signifiers of an inescapable fate because they represent a defined path from which you can't divert: in Zola's 'La Bête Humaine' for example and also in NORTH BY NORTHWEST, among many other films.

Even when he managers to get off the train, Vogel finds himself trapped by his environment:

Similarly, Alain Delon's characater Corey starts the film in jail but finds the outside world to be just as restrictive:

This visual motif of vertical lines is there throughout the film, and not always as obviously as the two examples above. It's there in the billiard hall for instance:

And in Jansen's (Yves Montand) hyper-stylised room:

The heist sequence itself, at a jewellery store in the Place Vendôme, is a masterpiece. Like I said before, Melville has made an almost abstract film so the heist is carried out in silence, except for one word, it lasts almost half an hour and is absolutely rivetting. You're almost invited to see the criminals carrying out their work as a form of self-expression.

|

| Abstract heisting |

You can see the trailer here:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)